For Grant Holmes, the secret is the cutter

The Atlanta Braves may have struck gold for a second straight year on the reliever to starter conversion front

Grant Holmes just put together the best start of his career.

The converted reliever, who was moved to the pen after six years of minor league ball across two organizations and then back to the rotation this spring, carried a perfect game into the fifth inning. Finally allowing a walk to open the fifth inning and then losing the no-hitter on a solo shot to open the sixth inning, Holmes finished with the second-longest outing of any Braves starter this season. Pitching 7.2 innings, Holmes was eventually charged with three runs on two hits and two walks, striking out four. It’s only the second time he’s gone more than five innings in his big-league career.

It wasn’t dominant - Holmes had just nine whiffs and finished with a below-average 27% CSW - but for a team that desperately needed length from a starter, Holmes delivered.

His slider is known across the league as a deadly pitch. Said Trea Turner of the Phillies after facing Holmes, “I think all of us had to adjust the first time through, because he was throwing pretty good sliders.” Manager Rob Thomson concurred, explaining “Holmes' breaking ball is really good. It was really sharp and late. The guys were having trouble picking it up.

But as good as his slider is, tonight’s success was all thanks to that cutter.

He changed his pitch mix tonight

In Holmes’ first two starts, he featured the fastball/curveball pairing as his primary weapons to lefties, mostly reserving the slider for righties.

But it’s also notable about what he almost never threw in those first two games - his cutter. Only three were thrown in his 193 combined pitches to the Dodgers and Phillies.1

Tonight, he threw seventeen of them in his 94 pitches.

Remember how we talked about Spencer Schwellenbach’s cutter working as a bridge pitch? The same idea works here, for both of Holmes’ breaking pitches. He used the cutter to both lefties and righties, throwing 10 cutter to lefties and 7 to righties.

And here’s what is amazing: Every single pitch after a cutter within the same at-bat was a strike or resulted in an out but two. He used it to set up Anthony Santander for a first-inning groundout on a curveball, as well as an eighth-inning lineout from Ernie Clement and a sixth-inning flyout from Nathan Lukes. The cutter itself picked up a few outs on its own - Vlad Guerrero Jr. flew out on it in the 7th inning, as did Andrés Giménez in the 2nd. Of his nine whiffs, two of them came on the cutter itself but two more came on the pitch immediately after the cutter, as well as two called strikes and three foul balls.

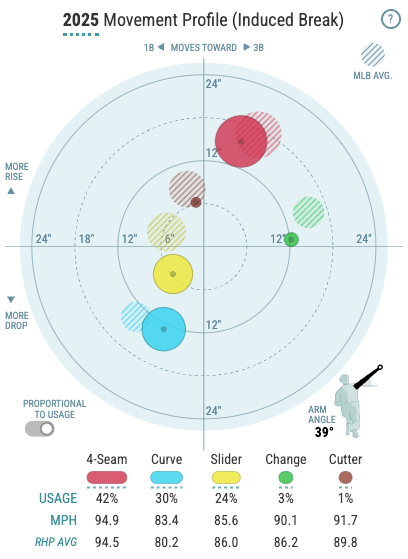

When you look at the season’s pitch plot (entering tonight), you can see why the cutter helps the rest of the arsenal.

The brown circle is the cutter, almost perfectly bridging the vertical distance between the slider and fastball and being in the middle of the horizontal movement between the curveball and four-seamer.

Truth be told, I don’t know why he wasn’t throwing it very much in the first two games, but I love that it’s back.

While he can’t overuse it - Holmes allowed a .467 average and .867 slug on 8.2% usage last year - this year’s version also has more drop and more horizontal movement than last year’s, allowing it to better disguise with both the fastball and the two breaking pitches out of the hand.

I thought the new kick change would be the pitch that unlocked everything for Grant Holmes. Instead, it was the cutter.

One to Jason Heyward of the Padres (groundout), one to Trea Turner of the Phillies (ball), and one to Nick Castellanos (swinging strike)

Great in-depth analysis as usual👏🏼🤓🍿