Why Minor League Park Factors Matter More Than You Think

How last season’s ballpark environments shaped Braves prospect performance

Context is king in the minor leagues.

When you consider the different paths a prospect can take to professional baseball - being drafted as a collegiate performer, coming straight out of high school, or signing as an international free agent at 17 - comparing the conventional statistics of any two players can be a fool’s errand. Even prospects at the same level and age may be at very different points in their development, depending on how their organization is choosing to improve them.

For example, the Atlanta Braves are well known for shelving a young pitching prospect’s curveball or other ancillary pitches in favor of leaning heavily on the slider early on. Think of it like a language immersion program. If all you have to get hitters out is a slider, you’re going to learn quickly, but the process can be messy. Your results, at least in the short term, might not be pretty.

And that’s before accounting for something else entirely: where those games are being played.

Baseball America just released its annual analysis of minor league park factors, and there are some fascinating conclusions to draw about the environments in which Atlanta’s prospects were developing last season. Let’s talk about it.

What are park factors?

In short, a measure of how hitter (or pitcher) friendly a given ballpark is. Run-scoring environments are evaluated and scaled to 100, with hitter-friendly parks above that figure and pitcher-friendly parks below.

The most common method compares offensive production at home versus on the road, isolating what a team’s home field does to their production by seeing how it changes when they leave that environment. By examining both that and how the road team’s offensive production changes, it’s easy to isolate how the park affected both teams relative to other environments in their specific league.

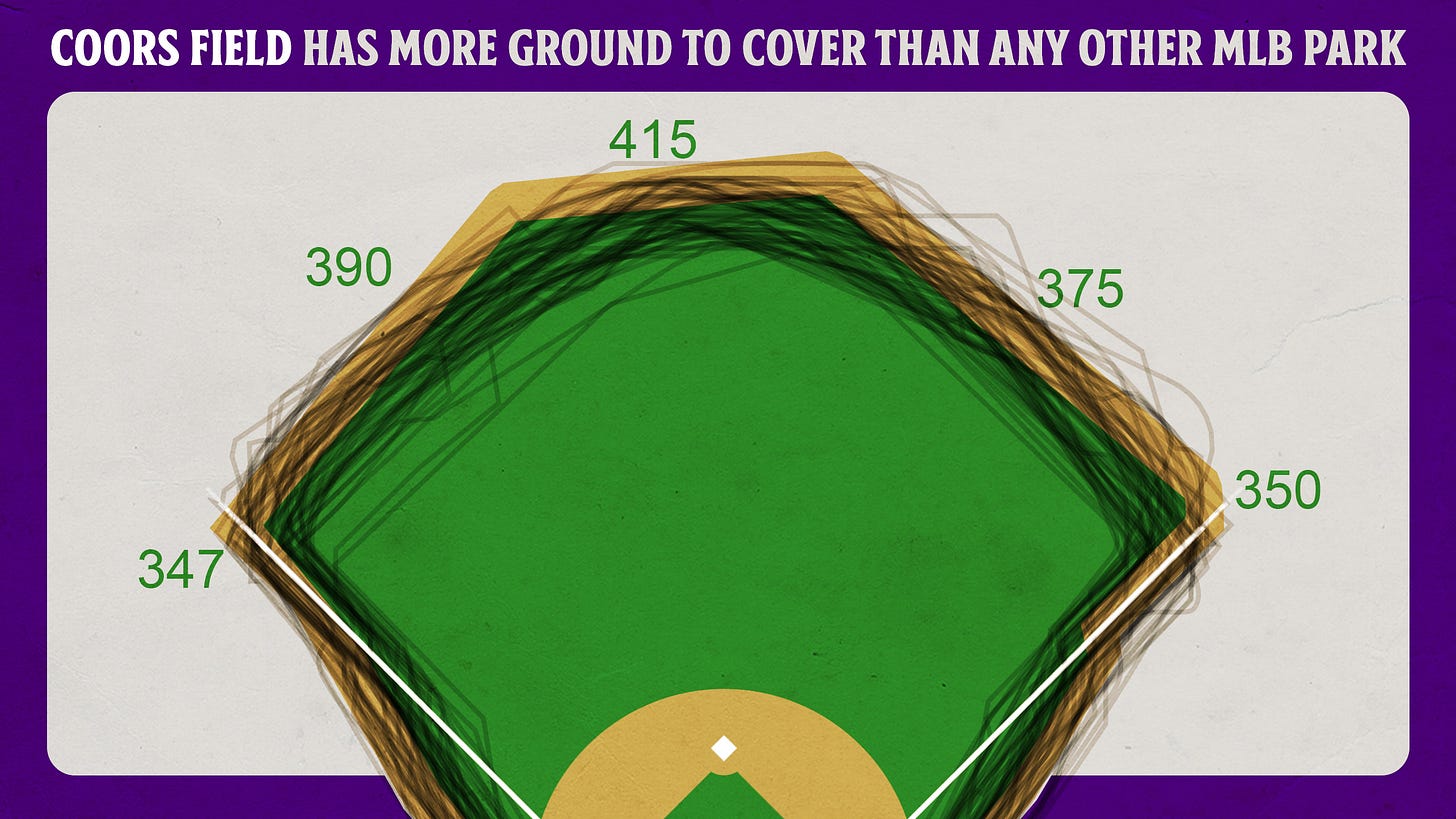

There are a lot of ways a ballpark can influence offense. Perhaps it’s the batter’s eye, with it being harder or easier to see incoming pitches.1 It could be the ballpark dimensions - Coors Field, the Rockies’ home park, gets labeled as an extremely hitter-slanted offensive environment because of the altitude (5,280 feet above sea level), but it has its most extreme park factors for extra base hits because of the absurd outfield dimensions:

Sometimes it’s slanted towards a specific handedness - Baltimore’s legendary Camden Yards was previously much more friendly to lefty power hitters (HR park factor of 125) than righty power hitters (HR park factor of 87) owing to the presence of “Walltimore”, a massive 13-foot high left field wall that was moved in nearly 26 feet and lowered to heights of between eight and six feet after the 2024 season.

There are a lot of factors that go into this - sometimes it’s obvious, like wall height and distance or altitude. But everything from wind (Chicago’s Wrigley Field wildly swings between a hitter and a pitcher’s park based on that day’s wind) to temperature (Seattle’s marine layer anecdotally suppresses power production) to even the time of day (shadows between the mound and home plate make it virtually impossible for hitters to accurately pick up a baseball out of the hand) or lighting can impact how a park plays.

How did Atlanta’s minor league parks do?

Overall, slanted towards pitching

Of the four ballparks in Atlanta’s system, Gwinnett’s Coolray Field plays the closest to neutral at an overall 97 park factor, so just slightly slanted towards pitching.

For simplicity, the base park factor number I cite will be for run scoring, but I’ll call out the home run number when appropriate.

Coolray Field is a difficult park to hit home runs in, though, with a home run park factor of 75, tied for 2nd-lowest in the entire International League behind Detroit’s affiliate in Toledo.

Last season, only five Stripers hit double-digit home runs, with veteran Eddys Leonard launching twenty and the next highest total on the team belonging to infielder Matthew Batten, with 11.

It’s important to point out here that some of this is sample size-influenced. For instance, Batten’s 11 homers came in 114 games/360 ABs, while veteran catcher Sandy Leon hit his 10 homers in only 58 games/187 ABs.

Here are the park factors for the rest of Atlanta’s full-season affiliates:

Double-A Columbus: 89 overall, 105 for home runs

High-A Rome: 84 overall, 32 for home runs (really)

Single-A Augusta: 104 overall, 141 for home runs

On Rome’s 32: That’s the lowest homer-related park factor I’ve ever seen over the years that Baseball America has been researching this. Double-A Mississippi’s Trustmark Park, which relocated to Columbus for the 2025 season, previously held the record with a 46. AdventHealth Stadium, home of the Rome Emperors, is 330 down the left-field line and 335 down the right-field line, maxing out at 401 in center field. That’s a tough task for any High-A hitter and one that’s right in line with dimensions in LA’s Dodger Stadium, but with a higher wall in Rome.

However, two things can be true at once: It’s not easy to hit for power in Rome, but the team’s talent had a lot to do with that, as well.

Across 4,111 at-bats last year, a grand total of 52 homers were hit by Emperors players and only eight of those were at home. But the team as a whole, road and away, hit only .220/.307/.301, so it’s not just the ballpark.

Additionally, Atlanta’s upper minors parks favor right-handed hitters over lefties, while Rome is rather neutral (no one can hit homers there) and Augusta slightly favors lefties.

There are a few clear conclusions we can draw about Atlanta’s prospects from these park factors.

What can we learn?

The first is that Braves pitchers logically have an easier time in this system than they might face in others.

We see this play out with some of Atlanta’s minor league opponents. The Rocket City Trash Pandas, Double-A affiliate of the Los Angeles Angels, usually have good pitching because not only does their park favor pitching (92 park factor), but their Triple-A affiliate is in the Pacific Coast League, which collectively has one of the most favorable offensive environments in the entire minors. Triple-A Salt Lake has a 112 park factor overall and 122 for home runs, so the Angels prefer to keep their top pitching prospects out of the level entirely unless they need to physically be close by for injury replacement reasons.

The counterpoint of this is that Atlanta’s hitters often have underwhelming power production in the minors, which could hinder their ability to land on top prospect lists. Michael Harris, who was voted 2022’s NL Rookie of the Year after hitting .297 with 19 homers in Atlanta, had just five home runs in almost 200 Double-A Mississippi plate appearances before being called up that May. Nacho Alvarez, no one’s idea of a power hitter, went from no AA homers in 202 plate appearances in 2024 to hitting 10 across his final 289 PAs in Gwinnett after a mid-season promotion.

Another takeaway here is that the significant change in home run factors between Single-A Augusta (141) and High-A Rome (32) means that the rise between levels might be a more daunting change than usual for some of the system’s burgeoning power hitters. Additionally, collegiate draftees entering pro ball straight into High-A, which is typically for multi-year starters from Division I, are faced with both the change from a metal to a wood bat and making it while entering a terrible power-hitting environment.

This doesn’t explain Alex Lodise’s entire post-draft struggles, but it likely didn’t help. The 2025 2nd-rounder hit just .252 with 42 strikeouts across 109 Rome plate appearances last season after the draft. Compare this with where he came from: The ACC. Dick Howser Field, home of Lodise’s Florida State Seminoles, grades out as a slightly hitter-friendly offensive environment on the whole and several ACC parks that Lodise visited, notably Georgia Tech’s Mac Nease Baseball Park at Russ Chandler Stadium (park factor of 120), were very hitter-friendly.

Context matters, but only to a point

Atlanta’s minor league parks clearly shape how prospects’ stat lines look, particularly when it comes to power. Pitchers in this system benefit from run-suppressing environments, while hitters, especially young ones trying to learn how to drive the ball, are often fighting uphill. That reality should inform how we read minor league numbers, not excuse them.

This is where the Braves’ internal evaluations matter more than public box scores. The organization has shown a willingness to trust quality-of-contact data, swing decisions, and pitch characteristics over surface-level results, whether that meant promoting Michael Harris aggressively in 2022 or trusting the ERA of Spencer Schwellenbach in 2024 when fast-tracking him to the majors.

Park factors don’t tell you who will succeed. They tell you where the noise is. And in a system where development goals often outweigh short-term results, understanding that noise is essential if you want to fairly evaluate the next wave of Braves talent.

The frustrating part is that Major League Baseball is not making that evaluation easy. While the league has taken steps to standardize minor league data collection this offseason (gift link), it has also capped how much data teams can collect beyond the minimum, and it has not committed to making that information publicly available the way it has at the major league level or even in Triple-A.

Maybe one day. Until then, context remains the most important tool we have - and the easiest one to overlook.

The Fenway Park batter’s eye is considered one of the best by MLB umpires, for what it’s worth, although I’ve heard good things about the Truist Park lighting on theirs.

You would think it would be a healthy and smart organizational move to try and mitigate extreme park factors, for fear that bad habits would develop in their MiLB players. Pitchers in a home park where it is nearly impossible to hit a home run get sloppy in leaving pitchers over the plate; hitters alter otherwise workable swings because they cannot get the ball out of the park the way they currently swing.

Great insight… Thanks for this analysis you can’t anywhere else. btw…you’re ball cap on yesterday’s podcast was phenomenal! I have to get one.